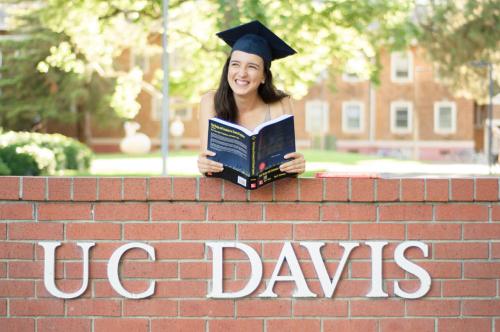

Daniela Barajas Ivey: A chemical engineer in aerospace

The best piece of advice M.S. student Daniela Barajas Ivey received as she earned her B.S. in chemical engineering at UC Davis was, “chemical engineering can be found in all disciplines.” She took this to heart and after joining the aerospace industry, she returned to UC Davis as a master’s student to study environmental control and life support systems (ECLSS) for human habitats in deep space.

“I’ve always loved space and I always wanted to find the perfect crossover between space and chemical engineering,” she said. “[ECLSS] is this incredible mix of both and the relationship is so beneficial and symbiotic. I’ve already seen it start and it’s growing into something incredible.”

Ivey works with Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Professor Steve Robinson. Robinson, a former astronaut, leads the Habitats Optimized for Missions of Exploration (HOME) space technology research institute, focused on developing technology to keep humans alive on deep space exploration missions. Her role is developing an ECLSS system that can turn wastewater and waste CO₂-rich air into breathable oxygen and drinkable water. Designing and optimizing this system is pure chemical engineering.

“There are a ton of definitions of chemical engineering, but the one that I resonate with most is using chemical processes to turn unusable materials into commodities,” she said. “That’s exactly what we’re doing—we’re turning unusable air and unusable wastewater into the biggest commodity in a space habitat: air and water.”

While the International Space Station currently has the most advanced ECLSS system, it’s still an open loop where potentially usable compounds are vented into space. This means it relies on oxygen and water shipments every two months. Next-generation deep space habitats won’t have this luxury, so they need to be more of a closed-loop system and improve their efficiency with the resources they have.

Ivey thinks the key is designing this system from the ground up, and she thinks an interdisciplinary academic environment like UC Davis is the perfect place to do this.

“That system has to work as a cohesive whole once it’s up in space, and what better way to make sure of that than to design it alongside all of the other researchers in other fields with all those interconnected activities in mind when you’re on the ground?” she said.

Undergraduate Opportunities

Ivey realized the possibilities chemical engineering held when she worked as an undergraduate researcher in Professor Tonya Kuhl’s lab. The lab bridges chemical engineering, biology and materials science. There, she studied the interactions between the two layers of a lipid bilayer, which encases a cell. Both Kuhl and Dr. Amanda Dang, a former Ph.D. student, mentored her, inspired her passion for learning and showed her that crossing disciplines was possible with chemical engineering.

“It was a life-changing opportunity,” she said. “I think one of the main things they passed on to me was a passion for learning and a passion for investigating and finding out everything that could be learned about a system. I’m so grateful to both Dr. Kuhl and to Dr. Dang.”

Ivey also learned a lot as part of Chem-E Car, a student team that builds a car powered by chemical reactions that has to perform precise movements. She managed the club’s lab space and gained a newfound understanding and respect for the work project management takes.

“You really have to understand the ins and outs of every single part of your project,” she said. “It’s definitely something that I’m using right now as I start research for ECLSS.”

Part of the Future

After graduating, Ivey became a spacecraft engineer at Maxar Technologies, where she worked on NASA’s Psyche mission to 16-Psyche, a possible early planetoid in the asteroid belt. She also made a point to return to career fairs at UC Davis as a recruiter to connect with students and inspire her fellow space-loving chemical engineers with her story.

“When they find out that I did my undergraduate in chemical engineering and I’m working in aerospace, it’s just incredible because it’s this light bulb moment for them and you can see it in their eyes,” she said.

Though she says Maxar was a dream job, she wanted to expand the foundation she’d built. She decided to return to UC Davis for graduate school to study ECLSS because of the strength of the aerospace engineering program and the collaborative spirit at UC Davis.

“One of the most impactful things that it [HOME] represents is this incredible cross-disciplinary teamwork that I think is necessary to establish a long-term presence in space,” she said. “To be able to work with Dr. Robinson as a graduate student is monumental and it inspires me every single day.”

Society’s renewed focus on space exploration promises significant opportunities in the budding ECLSS field for chemical engineers like Ivey in the near future. She’s thankful to be in a place like UC Davis where she’s able to work across disciplines to contribute to one of the next big things in aerospace.

“Chemical engineering is coming to space,” she said. “When we become a multi-planetary species, we’re going to have a completely different set of resources at our disposal. We’re going to have to take regolith from the moon and turn it into something useful, we’re going to have to take a CO₂-heavy atmosphere on Mars and make it into something useful. How we do that is a chemical engineering problem.”